Geoffrey Head was a member of our congregation who served as both its chair and its treasurer. This text is reproduced from his publication.

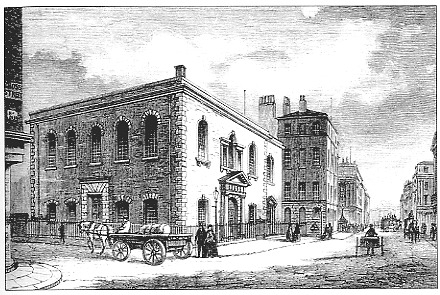

Cross Street Chapel, originally the “Dissenters’ Meeting House”, is the Mother Church of Non-Conformity in Manchester. If we exclude George Fox’s Quaker Meeting House at Swarthmore (1688), the original Chapel erected in 1694 on this site was probably the very first building erected for Non-Conformist worship in Lancashire.

For its origins we must look to the religious ferment during the period of the Commonwealth and the latter half of the 17th century. The founder of the congregation was Rev. Henry Newcome, Rector of Gawsworth under the Commonwealth, who became Preacher at the Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral) in 1657. He had been ordained as a Presbyterian and, like other Ministers of that ilk, he was generally favourable to the Restoration of Charles II, relying on the King’s expressions of tolerance. Hopes were not realised and the Act of Uniformity (1662) required all clergymen to give their “unfeigned assent and consent” to the Book of Common Prayer, the Thirty-nine Articles and to all other rites and ceremonies. On Black Bartholomew’s Day, 24 August 1662, two thousand clergy, including one hundred in Lancashire, were ejected from their livings. Amongst their number was Henry Newcome, as he found himself unable to deny the validity of his Presbyterian ordination. Restrictive legislation was enhanced. In 1665 an Act prohibited ministers from living within five miles from any place where they had preached.

For many years Henry Newcome thus conducted a proscribed and clandestine ministry. Yet he had powerful support. At the Collegiate Church his hearers had been numbered in many hundreds and he had the support of the common people. Furthermore he had married well into the Cheshire gentry and was close to such families as the Hoghtons of Hoghton Towers and the Delameres of Dunham. In particular he was a frequent and welcome guest of the influential Mosley family, Lords of the Manor, who lived at Hulme Hall. But, for a while, legislation obliged him to live in Worsley just outside the 5 mile limit. In 1670 he was able to return to Manchester, holding religious services in private houses, one of which was discovered and a £50 fine imposed, but in 1672 he obtained a licence and preached in his own house with open doors. Later he fitted up a barn in Shudehill for religious services. The spirit of persecution by the justices and others was however ever present and services were always liable to be broken up by supporters of Church and King. Circumstances changed with James II’s Declaration of Indulgence in 1687. Dissenting services became legal even during the hours of worship at the Collegiate Church, an assistant, Rev. John Chorlton, was appointed and the barn was enlarged. Henry Newcome was the spiritual adviser of Dame Meriel Mosley and he watched by her deathbed, This did not prevent Sir John Bland, a bigoted “Church and King” man, who had married the Mosleys’ daughter Ann, riding by the barn, creating a disturbance and breaking its windows.

William III was proclaimed in 1689, the Act of Toleration soon followed and the Dissenters were at last able to go forward in confidence. The congregation was large and included many wealthy and influential townspeople. Much to the dislike of the High Church party in control of the Collegiate Church, there grew a movement for the erection of a suitable meeting house. Henry Newcome himself was doubtful. Increasing age and thirty years of trial had taken their toll on his health and vigour, but he came round at last to support the project. A piece of land called Plungeon’s Meadow on the very spot where the congregation still worships was purchased and the building of the Meeting House began on 18 July 1693. The first religious service was held on 24 June 1694 with Newcome preaching on Exodus xx. 24 “Holiness to the Lord”. Sadly his infirmity increased. He was only able to take an occasional service in succeeding months and he died on 17 September 1695.

Amongst the most liberal contributors to the cost of the erection of the new Chapel were Sir Edward and Dame Meriel Mosley and their daughter Ann, notwithstanding the hostility of Ann’s husband, Sir John Bland. Ann succeeded as heiress to the Lordship of the Manor. After the death of Henry Newcome Ann decided to return to the established church and build a new parish church to meet the needs of the expanding township, but her Puritan background was still strong. It was said that she was “a thorough church woman, but belonging to that section which received the name of the low church party”. It was quite possible that, if Newcome had lived, St. Ann’s would not have been built. In the event her project came to fruition and St. Ann’s was consecrated in 1712. In a way it can be claimed that St. Ann’s is a daughter church of a Dissenting Meeting House. What is certain is that there has been a close relationship between church and chapel lasting to the present day. Both were from the outset identified with support for the Hanoverian succession in opposition to the High Tory and Jacobite sympathies of the Collegiate Church. The Meeting House indeed was soon to suffer for its political outlook. On 10 June 1715 a Jacobite mob proceeded to the chapel, smashed its doors and windows, overturned its pews and pulpits and left the whole place a wreck. The leader of the mob was Thomas Syddall, a blacksmith, who later joined the Jacobite army. On its defeat he was captured and executed at Knott Mill. It is said that his head was exhibited on the Market Cross within sight of the Chapel. The sum of £1,500 was awarded by Parliament in compensation for the damage and ordinary services were resumed in the Spring of the following year.

As the 18th century progressed the Chapel prospered under a succession of distinguished Ministers. Rev. John Chorlton was after a few years joined by Rev. James Conyngham. Together they conducted an Academy, although they were harassed from time to time by those opposed to dissent. The English Presbyterians were in general less disposed to dogmatism than other inheritors of the Puritan tradition. Henry Newcome and his fellow dispossessed ministers had not differed in theology from the established church – only in matters of church governance and ritual.

Congregations such as Cross Street had open trust deeds and this left them open to developments in belief. Under Rev. Joseph Mottershead (Minister 1717 – 1771) there began those doctrinal changes which led the congregation towards a Unitarian position. Mottershead himself was an Arian (holding that Christ was a separate person from God the Father, though still divine). Rev. John Seddon, Mottershead’s co-pastor from 1741 to 1769 and also his son-in-law, preached undiluted Unitarianism – one of his early sermons included the words “The Trinitarian doctrine, particularly, has been the disgrace of the Christian name and turned Christianity (contrary to its very nature) into a drab, subtle, undefinable science; a matter of difficult speculation and contentious sophistry; the occasion of vain jangling and eternal dispute; an engine of the imposition of tyranny; and the cause of bitter quarrels, furious contentions, mutual anathemas and the most cruel animosities”.

It is fair to say that the more prominent lay members of the congregation did not concern themselves with such forthright sentiments. The Unitarian cast of mind has always favoured a certain pragmatism expressed in concern for educational and social reform. In the last decades of the 18th century and the first decade of the 19th the co-pastors were Ralph Harrison (composer of the still well-known hymn tune “Warrington” and grandfather of the novelist Harrison Ainsworth) and Thomas Barnes. During their tenure a school to give free education to poor boys was established in the chapel premises. A more long-lasting project was the establishment of the Manchester Academy “on a plan affording a systematic course of education for Divines and preparatory instruction for the other learned professions as well as for civil and commercial life. The institution will be open to young men of every religious denomination, for whom no test, or confession of faith, will be required”. This was virtually the last of a long line of dissenting academies formed to provide higher education for dissenters still excluded from the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge. It survived moves from Manchester to York, back to Manchester, to London and finally to Oxford at the end of the 19th century to buildings designed by Thomas Worthington, the notable Manchester architect. Now a College of the University of Oxford, it still prepares students for the Unitarian and other ministries and also acts as a mature student college for the University.

Prominent in the formation of the Academy was Dr. Thomas Percival, eminent in natural philosophy, an essayist and the author of “Medical Ethics”. With Dr. Barnes he was responsible for founding the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society at the Chapel – this most famous society derived from Percival’s private dining club. He had a major role in bringing John Dalton to Manchester and was foremost in pioneering social health reform and the development of the Infirmary. He is commemorated by the “Percival Suite” in this new building. Dr. Barnes was succeeded by Rev. John Grundy, in whose ministry the Unitarian stance of the congregation was confirmed. It was said that his doctrinal discourse created in the town a religious ferment as it had never before witnessed.

As Manchester entered into the 19th century its place as the world’s first industrial city in the modern sense was becoming firmly established. It was the largest village in England, having neither corporate identity nor municipal underpinning to cope with the problems created by the enormous increase in industry and population. Its inadequate institutions were oligarchical and corrupt. Reform was required across the board. This could only be achieved by dedicated pressure from people with a social conscience, possessing the wealth and resources to tackle the vested interests head on. The Cross Street congregation was able to provide people to satisfy these requirements. Many manufacturers and merchants in the cotton and allied industries had become seriously rich. In Unitarianism they saw a freedom of religious thought which matched their laissez faire business philosophy: they were naturally attracted to the liberal Cross Street congregation and it was from Cross Street that an informal group was formed to tackle social and political reform. Dr. Michael Turner in his book “Reform and Respectability” reckons that this core group numbered about eleven in all, of which seven were Unitarians (including five from Cross Street Chapel). They met at the Cannon Street warehouse of Thomas and Richard Potter, wealthy cotton merchants and members of Cross Street. Other members of the Chapel involved included John Shuttleworth, Edward Baxter and John Benjamin Smith (all cotton merchants), John Edward Taylor (first Editor of the “Manchester Guardian”) and Fenton Robinson Atkinson (a prominent Manchester attorney). They controlled not only the “Guardian” but even more radical newspapers.

The endeavours of the group were assisted by the relaxed attitude of the dominant Cross Street Unitarians, never strongly sectarian, never allowing theological differences to prejudice co-operation with other Dissenters and reform movements. They used their wealth and respectability with discretion and judgement: yet they did not back off when their convictions took them to the very edge of the permissible or legal. Taylor was tried for libel (and acquitted) in 1819. Shuttleworth organised the defence of the Manchester 38 (plebian reformers accused of administering an illegal oath). Atkinson was ever present with legal advice and representations. All were active in the aftermath of Peterloo. These were not the middle class people castigated by Engels as moving out to the suburbs and washing their hands of the central working class districts and the problems of poverty. By the middle of the century many of their objectives had been achieved: Manchester had become a Borough, the First Reform Act of 1832 had extended Parliamentary representation, many social reforms had come to fruition. The agitators had become the new establishment. Thomas Potter became the first Mayor of Manchester on its incorporation and was subsequently knighted. Richard Potter was elected MP for Wigan in the first Reform parliament, Benjamin Smith became successively MP for Stirling and Stockport. Ten out of the first twenty-eight Mayors of Manchester were associated with Cross Street Chapel.

As the century progressed, the tradition of public service was maintained. The Unitarian Home Missionary Board was formed in the Chapel to train ministers for working class congregations. Of the thirteen original trustees of Owen’s College, later to become the Victoria University of Manchester, four were members of the Chapel, which also provided two University Treasurers and a Chairman of its Council. A Cross Street Trustee gave the University its first Women’s Hostel and members were active in the founding of the Manchester High School for Girls.

The Ministers of the Chapel by and large abstained from overt political involvement, but they were active in social work, underpinning the thrust of their laypeople, Especially notable was the long Ministry from 1828 to 1884 of Rev. William Gaskell, who exercised wide influence within and outside the Unitarian movement. He was heavily involved with the Manchester Domestic Mission Society set up by chapel members to provide a practical ministry to the poor “in such a way that at no time should any denominational or sectarian name or test be introduced”. He was active in the Lower Mosley Street Schools sponsored by his congregation to serve the areas of wretched housing around the River Medlock. A Fellowship Fund supported congregations in poorer locations. A nurse superintended by a lady of the congregation was financed to visit poor families near the town centre. The Cotton famine presented particular challenges. William Gaskell was committed to working class education and the Mechanics Institute movement and he had numerous literary interests including the Lancashire dialect and his Chairmanship of the Portico Library from 1849 to his death in 1884.

William Gaskell was supported in his endeavours by his wife, the novelist Elizabeth. The congregation in general remained firmly behind the couple in the controversies relating to “Ruth” and “Mary Barton” and in particular “The Life of Charlotte Bronte” despite a few middle class qualms as to the propriety of raising in print some of the issues confronting conventional Victorian values. William became a legend in his own lifetime, in the Chapel, Unitarianism generally and the life of the City. When he completed fifty years of his Ministry at Cross Street in 1878 there was a soirée in Manchester Town Hall attended by over one thousand people. Apart from a lavish gift of silverware from the congregation, a large sum of money was raised and this was applied at William’s request to the founding of a scholarship for ministerial students at Owen’s College (now Manchester University).

Yet times were changing. The Chapel, having played a determining role in the rise of Manchester, was to find itself a victim of its own success. The town houses of the wealthy manufacturers and merchants were turned into warehouses and their owners moved into the suburbs and further afield. By the 1860s the trustees and leading congregational members were increasingly professional men – comfortably off but with finite resources compared with the previous generations. The membership list was still healthy, but attendances at Sunday services were declining – pew holders who had removed from the city centre were reluctant to travel back for a service, when they could attend another place of worship nearer to their new home. The decline in the influence of the elite body of Trustees was manifested in a move towards a more democratic form of government and a Chapel Committee was formed for the first time.

The first decade of the 20th century was a difficult one for the Chapel. There is a consensus of belief that Free Church adherence in Britain peaked around 1906. Cross Street Chapel had the additional problem of the continued flight of the middle classes to the suburbs and beyond – the North West was still the Unitarian heartland and there were plenty of local chapels to which they could adhere. But there were other threats.

Manchester Corporation wished to close the graveyard and acquire part of the Chapel site for a proposed widening of Cross Street In July 1914 a Manchester Improvement Bill came before a Committee of the House of Commons authorising the Trustees to pull down the Chapel, remove the human remains and sell the land for building purposes. The clause was contested, but was carried. A year or two previously it had been announced at a meeting of the City Council that the Chapel was to be given up as a place of worship. Possibly the Trustees had it in mind to devote the proceeds of the sale of the site to the erection of a successor chapel in one of the developing residential areas. However, the Great War broke out within three weeks and the project went into abeyance.

After the war there came a remarkable change of fortune. In 1919 the Trustees appointed Rev. H. H. Johnson to the vacant pulpit. He proved to be a charismatic Minister, filling the Chapel, said to hold two thousand people, Sunday after Sunday and also at Wednesday lunchtime services. He introduced The Wayside Pulpit for the first time into this country. The messages were renewed each week and published as a booklet at the end of each year. It became a feature of Manchester life and was widely taken up throughout the country. Originally all the messages were composed by the Minister – a simple one that achieved much reproduction in all sorts of ways was “Don’t worry – it may never happen”. Sadly Mr. Johnson had to resign the pulpit because of ill health in 1929 and World War II broke out during the ministry of his successor.

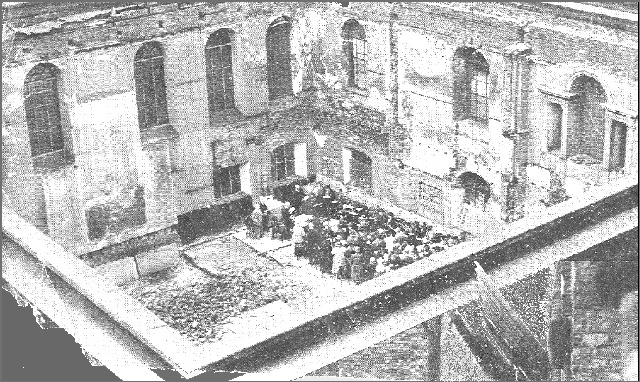

Ruins of the original chapel in 1940.

In 1940 the old Chapel was destroyed by enemy action – by fire bombs. There was no interruption of worship. Amongst the ruins a prefabricated building was erected and there the congregation carried on as best it could until the late 1950s, when a new building was erected, partly financed by War Damage payments, partly by an Appeal. The congregation gradually gathered strength in the new building, but in a number of ways it proved far from ideal. At the time of the rebuilding the accepted wisdom favoured dual purpose church buildings with worship areas readily convertible for social purposes. By the late 1980s it was apparent that the resumption of Cross Street’s outward looking role was impracticable in the 1959 building. There was much waste of space in the rather bleak main chapel with inadequate ancillary accommodation for congregational and social purposes. The City Centre Churches had come together on an ecumenical basis to face up to the needs of a multicultural society and the Cross Street congregation sought to provide a building able to meet the challenge of a new Millennium. The wider Unitarian movement was also in need of a regional centre to support development work in the North West with appropriate technological and other facilities.

The Trustees were determined to retain the freehold of their historic site and retain a frontage overlooking St. Ann Street. This pointed to a Chapel with offices above. Provision was made for a concourse surrounding a circular Chapel, an office, a resources centre, a choir vestry/small worship room and a divisible community suite with kitchen facilities available for meetings, social responsibility work and outside religious, charitable and cultural organisations. The mezzanine floor contains a high quality board room, a Minister’s Vestry, a congregational/small meeting room, a plant room and the Chapelkeeper’s flat. There is ample toilet accommodation and the disabled facilities include a lift and a loop hearing system. The Resources Centre contains a high specification computer installation and a range of advanced audio visual equipment. The overall concept was to provide a building where numerous activities could take place, but at all times provide a consciousness that there was a place of worship at the core. The naming of the rooms recognises the Chapel’s heritage – the 17th century is remembered in the Newcome Vestry, the 18th century in the Percival Suite, the 19th century in the Gaskell and Relly Beard Rooms and the 20th century in the Kenworthy Room. Relly Beard was the Minister of the former Strangeways Church, a prominent educationist and the first Principal of the Home Missionary Board (now the Unitarian College) in 1854: he was a close colleague of William Gaskell. Portraits of both Gaskell and Relly Beard are to be seen on the mezzanine floor. The Kenworthy Room gives tribute to Rev. Fred Kenworthy, Minister of Cross Street Chapel 1950-55, later a President of the General Assembly and Principal of the Unitarian College. In the concourse there is to be seen a board listing the Ministers of the congregation since Henry Newcome. The last two names are those of Rev. Denise Boyd, the Chapel’s first woman minister who had much to do with the design and concept of the new place of worship, and Rev. John Midgley, the present incumbent, who has safely brought the congregation from Cavendish House round the corner in Pall Mall, its temporary home during rebuilding.

In this new Chapel the congregation has problems undreamed of by its illustrious predecessors. Public transport is worse now than it was a hundred years ago. Sunday shopping renders car parking difficult. In a secular society there is a general and continuing decline in church attendance. Nevertheless, come what may, the congregation will continue to be governed by the attitudes set out by two writers not from their own religious background.

From Michael J. Turner “Reform and Respectability“ “The Unitarians tended to hold relaxed attitudes to doctrine, believing that one’s conduct and lifestyle were more important than any rigid adherence to particular theological tenets. At Cross Street there was no doctrinal test on ministers or members of the congregation. The attitude was liberal, tolerant and informal”.

From Adrian Hastings “A History of English Christianity 1920-1985″”Cross Street Chapel, the original Dissenters’ Meeting House, turned over the centuries Unitarian. Here was dissent at its most secular, its most assured, its most unparochial . . . it had retained its liberal conscience”.

Select bibliography

The main and primary sources relating to Cross Street Chapel are the Trustees’ and Congregational Minute Books held at the Chapel or John Rylands Library of the University of Manchester, together with the Annual Reports, programmes, tickets and other literature at the Chapel, relating to the congregation, the Lower Mosley Street Schools and the Manchester Domestic Mission Society. >P> Frederick Engels “The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844” is a key source for working class conditions in Manchester during the first half of the 19th Century.

Michael J. Turner “Reform and Respectability” (Chetham Society 1995) covers the impact of Cross Street Chapel on the pressures for Reform. Other useful references to the Chapel are to be found in “Manchester in the Victorian Age” by Gary S Messinger (Manchester University Press 1985), “Boomtown Manchester” by Ann Brooks and Bryan Haworth (Portico Library 1993), “The Unitarian Contribution to Social Progress in England” by R. V. Holt (Lindsey Press 1938), “Truth, Liberty and Religion” (Manchester College, Oxford 1986).

“The Letters of Mrs. Gaskell” ed. Chapple/Pollard (Manchester University Press 1966) and the numerous biographies of the novelist including those by Jenny Uglow and Winifred Gerin and the study of her “Early Years” by John Chapple give further material.

“William Gaskell 1805-84” by Barbara Brill (Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society 1984) is another source. The standard history of the Chapel to 1884 was written by Sir Thomas Baker, secretary to the Trustees and twice Mayor of Manchester (published by Simpkin Marshall): although it was written practically at the end of William Gaskell’s long and distinguished ministry the only reference to him is “The Rev. William Gaskell was chosen as Mr. Worthington’s successor in 1828 and his ministry still continues” – there had been a quarrel about a change of hymn book, always a contentious issue in Unitarian chapels!

Ministers of Cross Street Chapel

Henry Newcome 1662 – 1695

John Chorlton 1687 – 1705

James Coningham 1700 – 1712

Eliezer Birch 1712 – 1717

Joseph Mottershead 1717 – 1771

Joshua Jones 1725 – 1740

John Seddon 1741 – 1769

Robert Gore 1770 – 1779

Ralph Harrison 1771 – 1810

Thomas Barnes 1780 – 1810

John Grundy 1811 – 1824

John Gooch Robberds 1811 – 1854

John Hugh Worthington 1825 – 1827

William Gaskell 1828 – 1884

James Panton Ham 1855 – 1859

James Drummond 1860 – 1869

Samuel Alfred Steinthal 1870 – 1893

Edwin Pinder Barrow 1893 – 1911

Emanuel L. H. Thomas 1912 – 1917

Henry H. Johnson 1919 – 1928

Charles W. Townsend 1929 – 1942

F. H. Amphlett Micklewright 1943 – 1949

Fred Kenworthy 1950 – 1955

Reginald W. Wilde 1955 – 1959

Charles H. Bartlett 1960 – 1967

Kenneth B. Ridgway 1969 – 1971

E. J. Raymond Cook 1972 – 1987

Denise Boyd 1988 – 1996

John Andrew Midgley 1997 – 2008

Jane Barraclough 2008 -2014

Cody Coyne 2014-